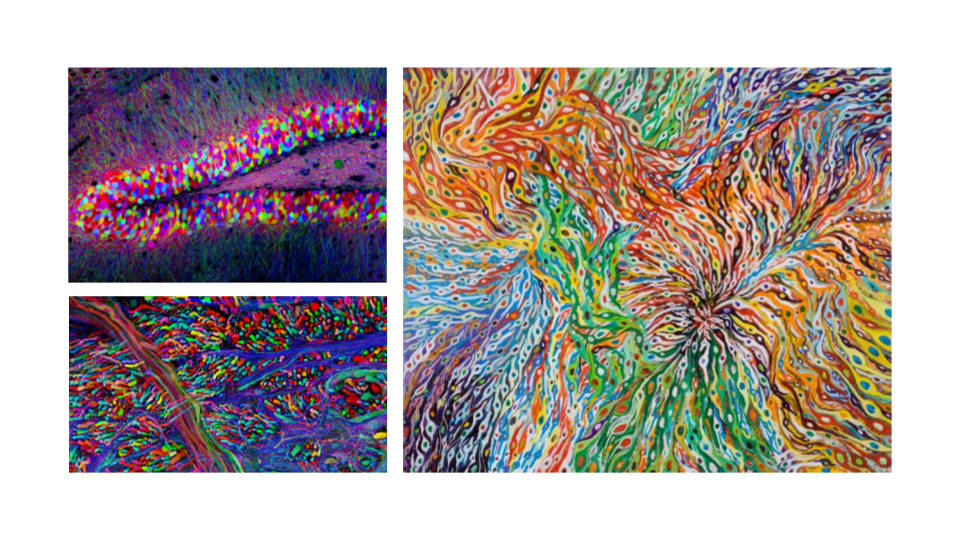

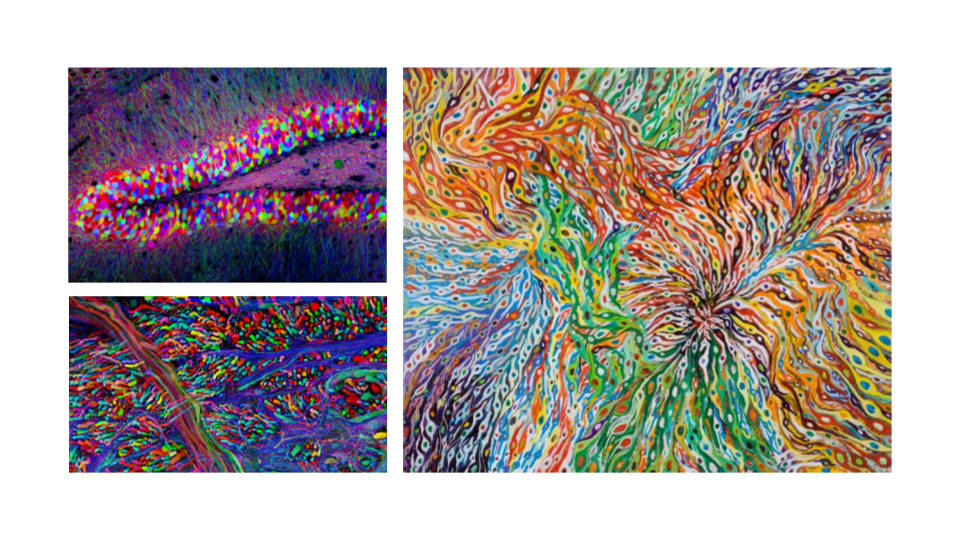

In the parable of the blind men and the elephant, each paid attention to a different aspect of the creature. The brain may do something similar by mapping out the qualities of perceptions, experiences and abstract concepts along various dimensions, with the help of the same system that it uses to map out physical spaces.