Sublime

An inspiration engine for ideas

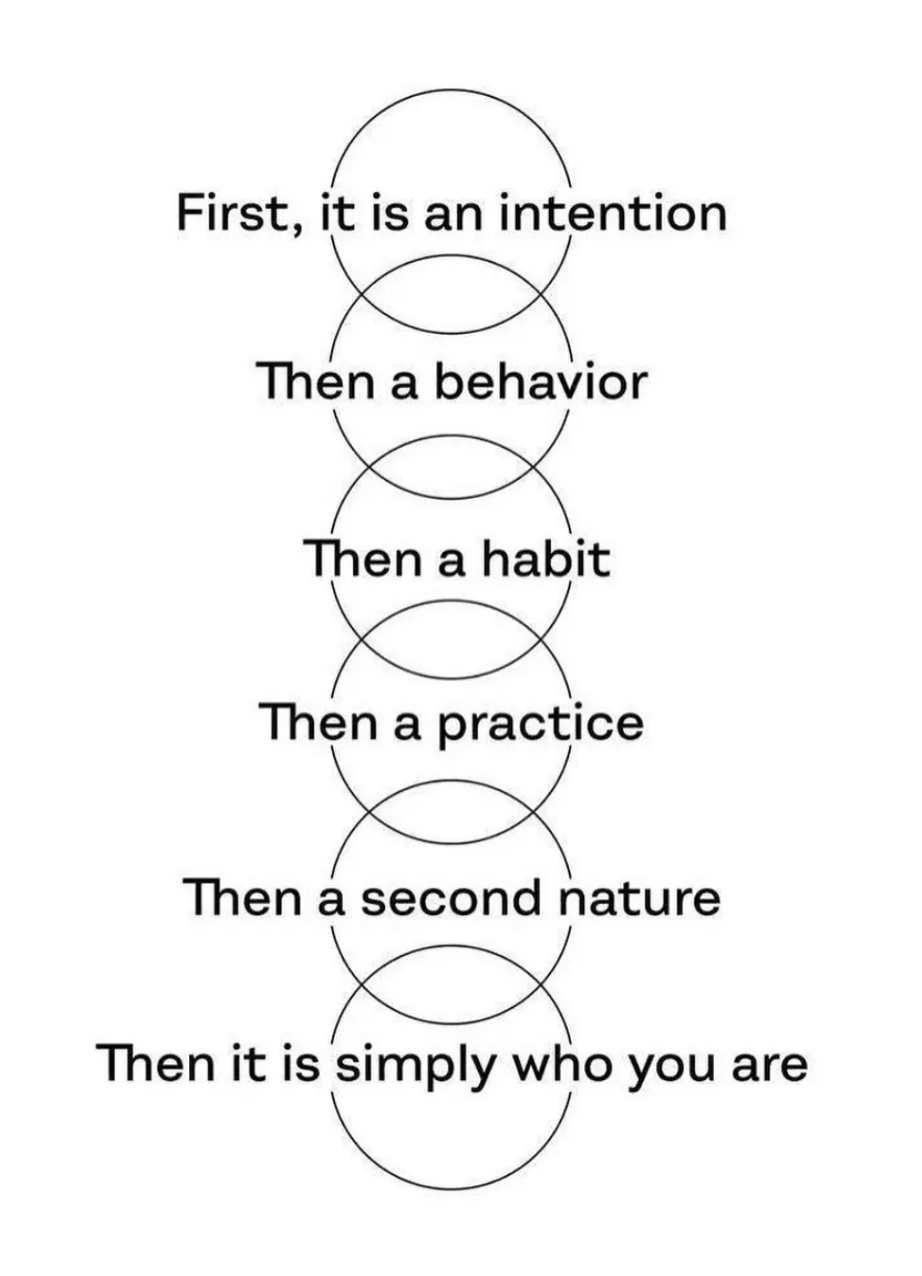

Creativity is the quality that you bring to the activity that you are doing. It is an attitude, an inner approach — how you look at things. Not everybody can be a painter — and there is no need also. If everybody is a painter the world will be very ugly; it will be difficult to live. And not everybody can be a dancer, and there is no need. But

... See more

It’s hard. I don’t know how to resolve the conflict between Information wants to be free and Writers deserve to be paid . But it’s worth noting that the internet of yesteryear, where almost every article was free to read, was also the internet that drastically reduced the value of highly researched, carefully argued writing. That internet helped... See more

Celine Nguyen • we've created a society where artists can't make any money

Human cognitive limitations, feelings of intellectual inadequacy, and why AI’s lack of these limits is profoundly exciting

TRANSCRIPT

Well, I don't know if you have this experience. I have this experience all the time. Well, two experiences I have all the time.

One is just like, I know I ought to be able to do this, but like, I just can't, like, it's going to take too long. You know, I want to write this thing, or I want to like, whatever, I want to have this theory on this

... See more