Joel Nessim

@joelnessim

Joel Nessim

@joelnessim

The scholar and his cat, Pangur Bán

(Translated from the Old Irish by Robin Flower.

Click here for the original with a literal translation.)

I and Pangur Bán my cat,

'Tis a like task we are at:

Hunting mice is his delight,

Hunting words I sit all night.

Better far than praise of men

'Tis to sit with book and pen;

Pangur bears me no ill-will,

He too plies his

William Blake Engraving

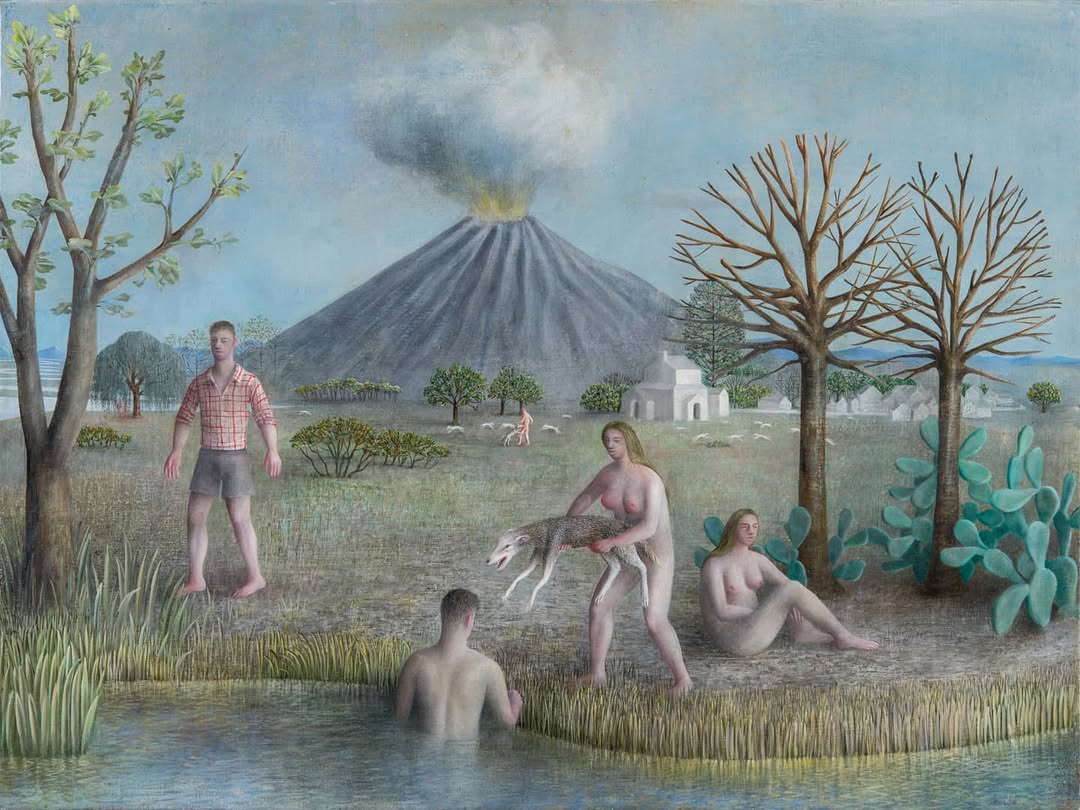

Apple Gatherers Stanley Spencer

website and