weekly Go Flip Yourself

roundup links to share every week on k7v.in and flana.substack.com

weekly Go Flip Yourself

roundup links to share every week on k7v.in and flana.substack.com

Our brains can’t store every observation, thought or perception that passes through and that isn’t a bad thing. Constraints and selections are what allow us to stay sane in a world of complete sensory overload.

We do have a problem of stuff. which is why we’re building objet.cc

Change and growth cannot be bought, only earned through the difficult business of removing all of the dross and faulty thinking (that’s been imposed on us) and getting to the core of things:

Love, service, creativity, community, relationships, family.

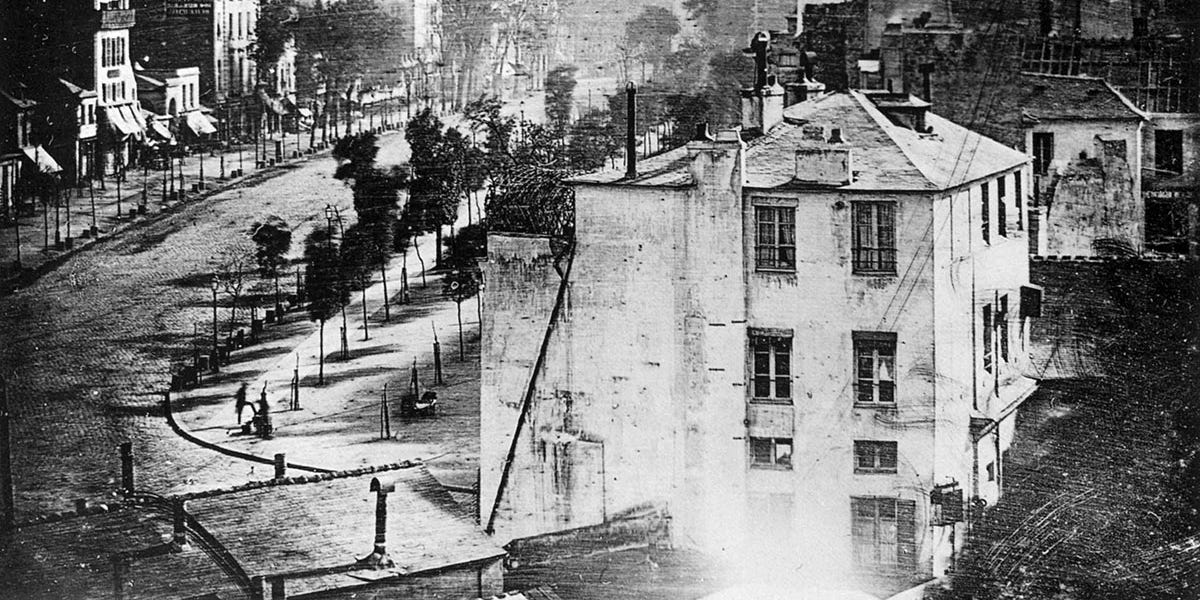

Archiving is powerful.

Coming into communion with an object means forming a relationship together.