developing your sense of taste

Why Cringe Tolerance Separates Builders from Non-Builders

medium.com

Here for the Wrong Reasons | Are.na Editorial

are.na

All of this brings me to the title of this piece, “Here for the wrong reasons,” which I have to come clean about. Earlier this year, I was in a mode where I was feeling particularly annoyed at a certain type of person online. The easiest way to describe this type of person is someone whose interests are more strategic than personally intuitive. A person whose interests accumulate with an awareness of how they will reflect back onto them. A person who follows nodal points not from an innate desire, but from the expectation of some kind of reward, social or otherwise.

Or to put it in different terms, a person who is here for fame and not for love.

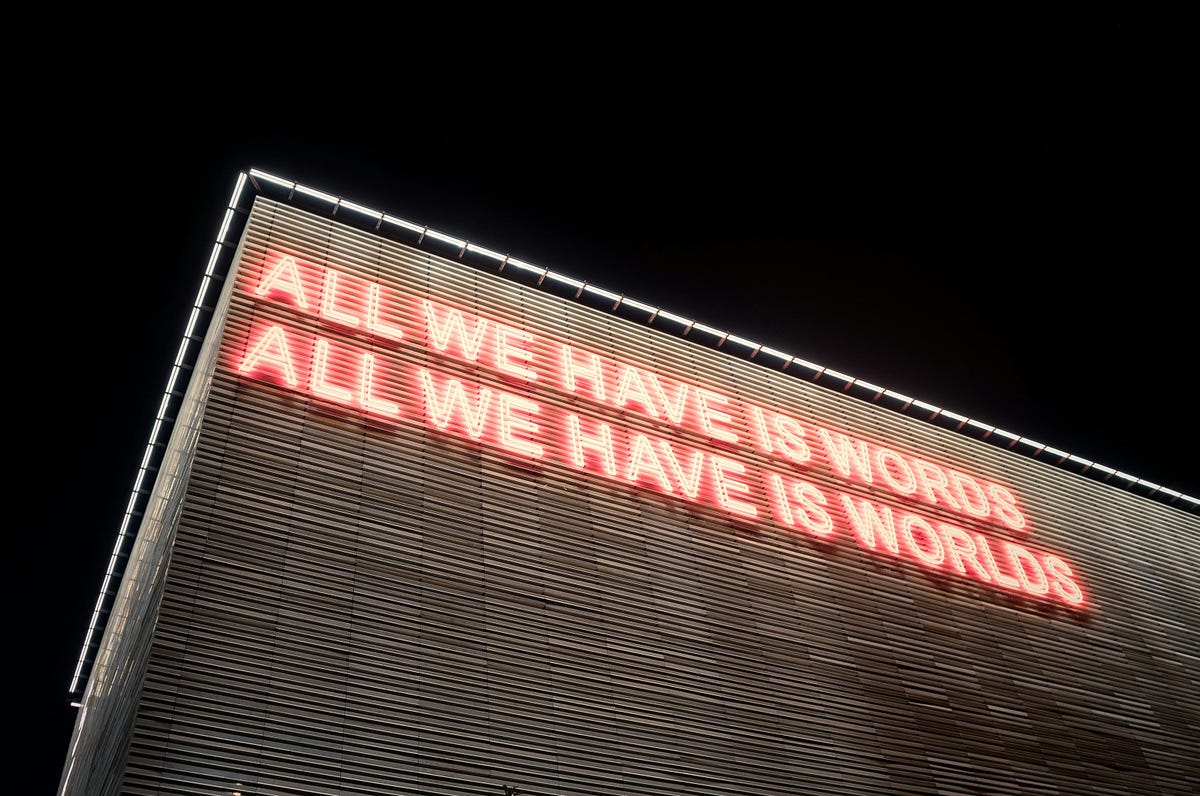

Algorithms pervert one’s attention. An atmosphere that promotes being performative does as well. Part of what I’m trying to grapple with is how software or platforms or environments can get in the way of one’s own feeling of being connected — not to other people necessarily, but to your own intuitive radar.

There is this tendency to think about software, especially software that is more on the “tool” side as something that augments your ability as a human. What I keep coming back to is that I really don’t want that at all. I like feeling connected to things and unencumbered. I like feeling the humanness of things and my own human relationship to things. I want to be able to feel true attention, or at the very least, the possibility of it.

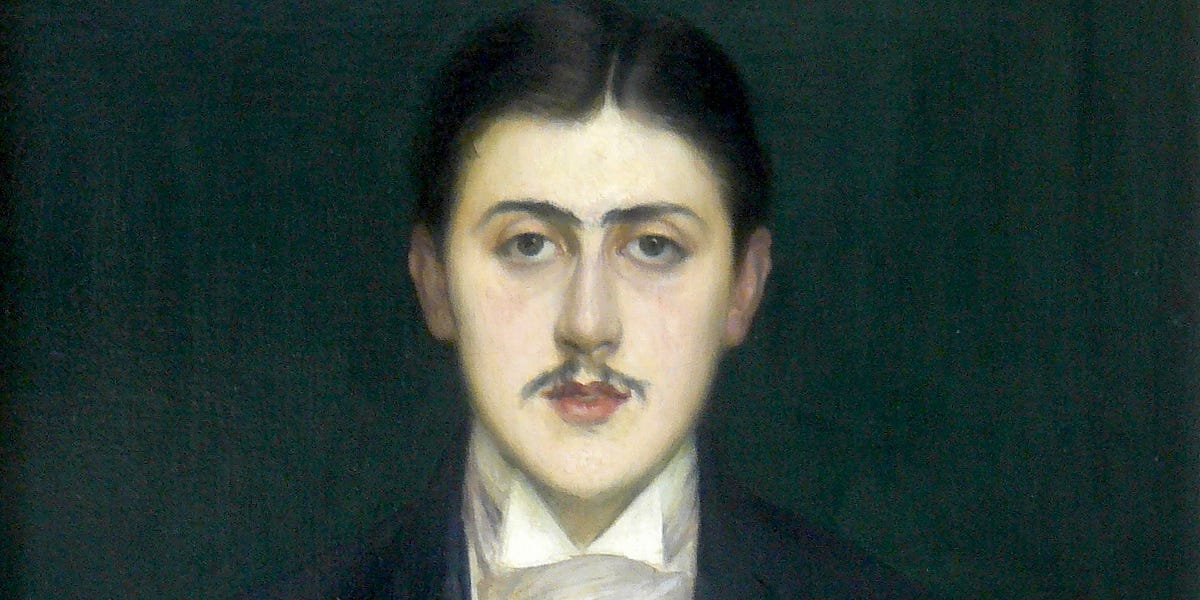

Reading In Search of Lost Time, I realized that Proust described certain experiences—being conscious, perceiving reality, observing the world, encountering other people—with a kind of trembling, vital energy I had never experienced before.

Ottessa Moshfegh once said to Bookforum, “A novel is a literary work of art meant to expand consciousness.” (In that sense, Proust may be more transformative than a psychedelic trip—though the most effective approach, perhaps, might be to combine the two.5)

The function of criticism, for him, wasn’t to prescribe or proscribe; it was to “connect.” To seduce and please, rather than épater la bourgeoisie…While criticism, for Baudelaire, was necessarily “partial, passionate, political,” for Schjeldahl, it was—above all—pleasurable. Art, he claimed, was “about 100 percent” pleasure.You have to do what Schjeldahl did and communicate the experience of looking at paintings. To make people understand why you might invest your time in these experiences…You have to describe the blooming, buzzing experience of coming into awareness with art and why it might be desirable, more desirable and fulfilling than things that are easier.

Taste is more like love than education

What I needed, as a young reader, was for someone to tell me: These are the books that have the capacity to change you—to reprogram your phenomenological and philosophical approach to living—to transform you.Taste is more like love than education

What I needed, as a young reader, was for someone to tell me: These are the books that have the capacity to change you—to reprogram your phenomenological and philosophical approach to living—to transform you.

“Algorithms pervert one’s attention,” Broskoski notes, but “an atmosphere that promotes being performative does as well.”