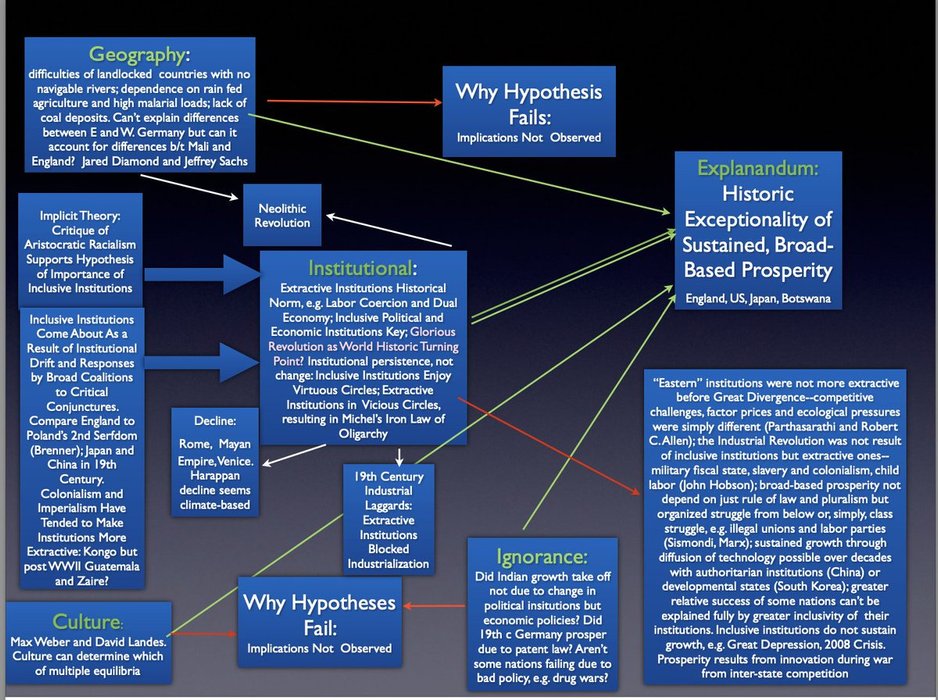

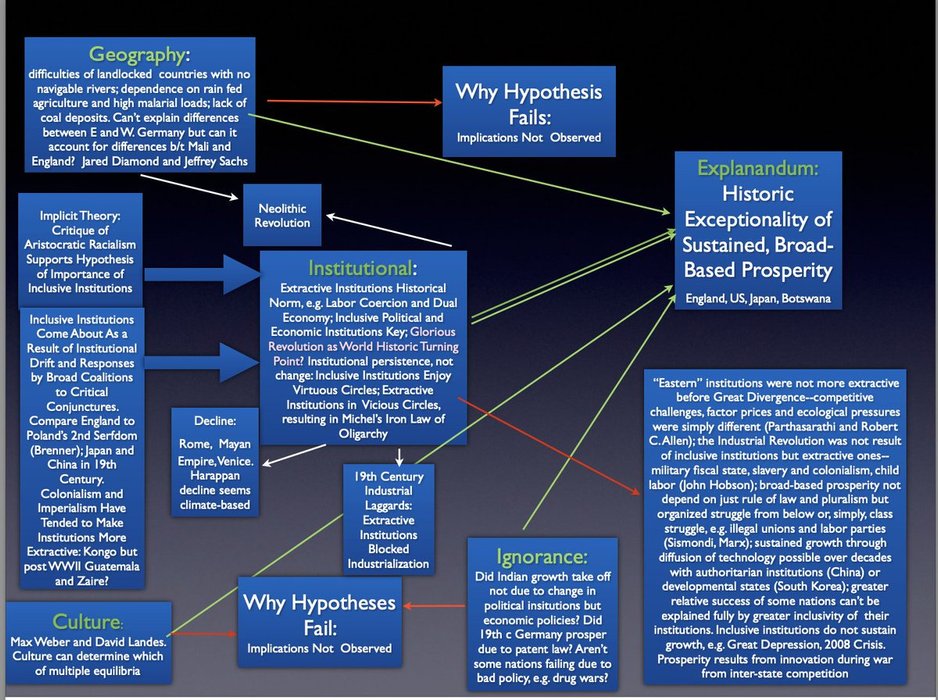

Why Nations Fail is a bit longer than The Communist Manifesto, but it is essentially The Bourgeois Manifesto. Merchants having become wealthy from the Atlantic trade win property rights in England, already primed for this breakthrough. Resultant regime called inclusive, though the merchants were primarily slavers. They will underline however that these inclusive Western societies strengthened the worst, most extractive features in the colonies over which they ruled, but deny that colonialism powered the wealth of the West. Colonialism however still plays a role in the poverty of the rest of the world. But prosperity is due to property rights and innovation, and not exclusive to the West (consider Botswana and Japan). Newcomen, Watt, Boulton, Stephenson--from the middle classes-- tinker, incentivized by IPR. The Industrial Revolution results and yields broad-based prosperity. The State can't be captured, though, by existing businesses. Entrepreneurs incentivized by property rights have to be free to shake things up again; otherwise declining marginal returns and stagnation set in. Institutions matter, not geography, culture, or good public policy. Their most interesting case study is not The Glorious Revolution for which they are most famous but the spread, reversal and, in places, maintenance of the Napoleonic Codes. With good institutions, societies can separate themselves from societies similar in culture and geography; good institutions can even reverse what were considered geographic deficits. They had a good debate with Jeffrey Sachs about whether their theory is too reductive; the regressions are based on a shocking paucity of data. But before it was fashionable to say with Kiernan Healy, fuck nuance, they were fucking nuance. I attach a crazy slide I used ten years ago to show that they implicitly use the hypothetico-deductive mode of explanation. They show that their institutional hypothesis can not only best account for the explanandum (why nations succeed), it has excessive explanatory power while the rival hypotheses have implications that are not observed. In the following book Shackled Leviathan Acemoglu and Robinson are less focused on property rights and the structure of the state but now on freedom in civil society and social movements, considered key to break up the state's tendency towards absolutism and economic monopoly power. In Acemoglu and Johnson's latest book, power asymmetries are more sharply focused on. Leaving technological choice and levers of society to the most economically powerful suffering from a grandiosity and narrowness of vision won't give us productivity bandwagons but today's over-automation with only so-so productivity gains, workplace surveillance to sweat labor as a way of reducing unit labor costs, and a click-driven social media antithetical to democratic deliberation. What began as a defense of bourgeois institutions has now become a call for bottom-up worker empowerment. The forms of empowerment are limited: unions, representation on corporate boards, more worker- rather than capital-friendly tax policy. Interdisciplinary studies has been massively enriched by their work and the sharp debates around it. Their work provides arguably the most important justification that we have for a Program such as ours--along with the next year's Nobel Prize winner, Thomas Piketty😉 The Prize is richly deserved. I am pretty sure I have been one of the first to teach each of these books at Cal. Daron was kind enough to share the galley of Power and Prosperity with me. I think Noah Smith's criticism, widely circulated on twitter, is terrible.

Power and Progress: Our Thousand-Year Struggle Over Technology and Prosperity

amazon.com